Image Gallery

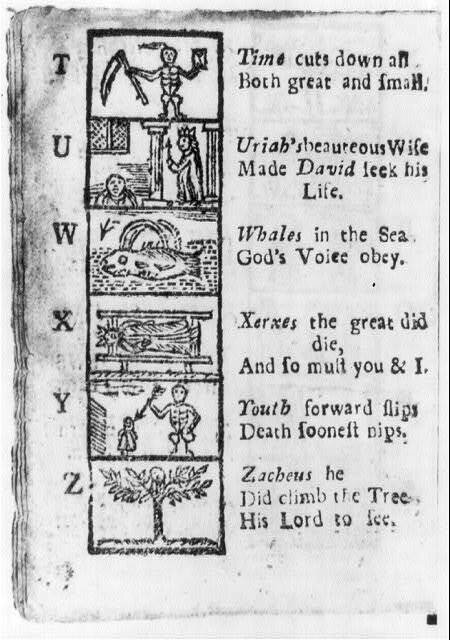

'Xerxes the Great did die, and so must you and I'

Generations of American schoolchildren, from the 1690s until well past 1800, associated the letter X not with xylophones but with the name of an ancient Persian emperor. (Two million copies of The New England Primer, a textbook teaching children to read, are believed to have been sold during this time). References to ancient Persia were commonplace in colonial America — a kind of cultural literacy that endured well into the 1950s, but has now all but vanished.

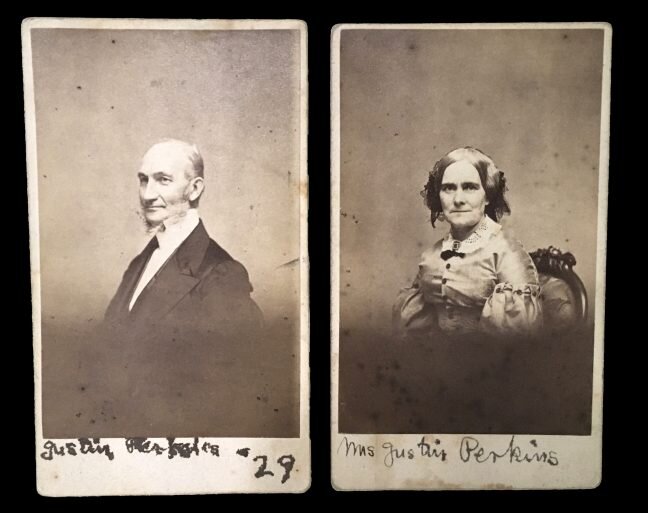

Justin and Charlotte Perkins (first Americans to live in Iran)

The Presbyterian missionaries arrived in 1833, with Charlotte heavily pregnant. They quickly established a boys’ school in Urmia and produced the first Syriac translation of the New Testament, still widely used by Assyrian Protestants. Their arrival ushered in a century of American missionary activity in Iran.

(Amherst College Archives & Special Collections)

American Presbyterian cemetery (1855), Iran

In the hills overlooking the city of Urmia, in a tiny village called Seir, this collection of graves might just be one of the most neglected repositories of American remains anywhere in the world. Around 50 Americans are buried here — most of whom spent their entire lives working and living in Iran. American Presbyterian missionaries were the driving force behind the first major phase of US-Iran interaction. The mission in Urmia operated from 1835 to 1935.

(author photo, 2009)

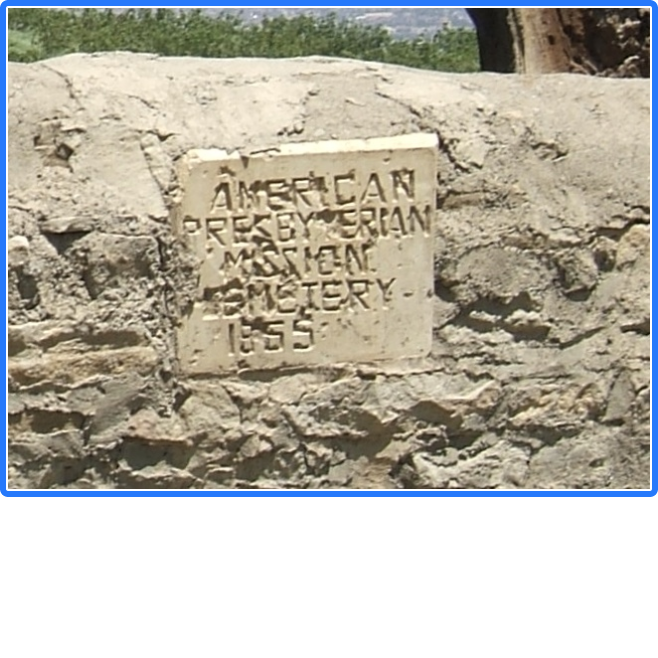

American Presbyterian cemetery (1855), Iran

In the hills overlooking the city of Urmia, in a tiny village called Seir, this collection of graves might just be one of the most neglected repositories of American remains anywhere in the world. Around 50 Americans are buried here — most of whom spent their entire lives working and living in Iran. American Presbyterian missionaries were the driving force behind the first major phase of US-Iran interaction. The mission in Urmia operated from 1835 to 1935.

(author photo, 2009)

American Presbyterian cemetery (1855), Iran

In the hills overlooking the city of Urmia, in a tiny village called Seir, this collection of graves might just be one of the most neglected repositories of American remains anywhere in the world. Around 50 Americans are buried here — most of whom spent their entire lives working and living in Iran. American Presbyterian missionaries were the driving force behind the first major phase of US-Iran interaction. The mission in Urmia operated from 1835 to 1935.

(author photo, 2009)

American Presbyterian cemetery (1855), Iran

In the hills overlooking the city of Urmia, in a tiny village called Seir, this collection of graves might just be one of the most neglected repositories of American remains anywhere in the world. Around 50 Americans are buried here — most of whom spent their entire lives working and living in Iran. American Presbyterian missionaries were the driving force behind the first major phase of US-Iran interaction. The mission in Urmia operated from 1835 to 1935.

(author photo, 2009)

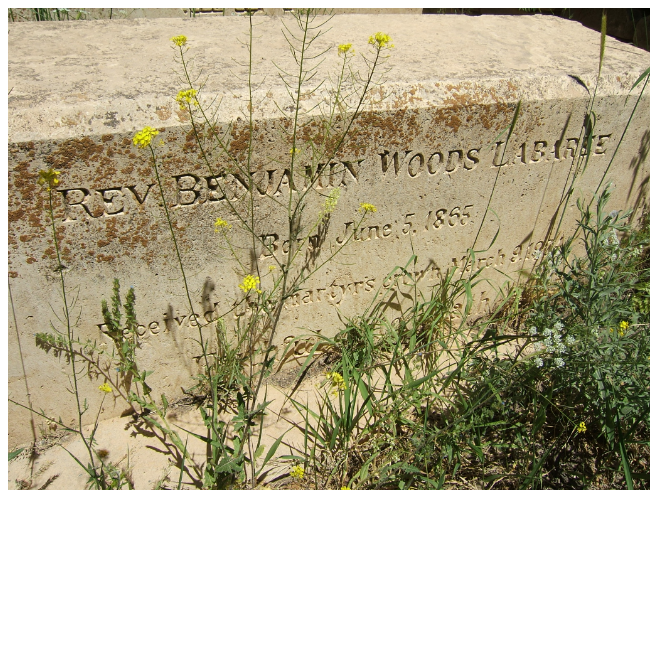

Grave of Rev Benjamin Labaree (murdered 1904), American cemetery, Seir

A prominent American missionary in Iran, Labaree was murdered by Kurdish bandits in lawless terrain near the northwest frontier. The inability of the Iranian government to bring his killers to justice escalated into the first significant diplomatic dispute between the United States and Iran — with President Theodore Roosevelt even hinting at military action.

Graves of children (some of them unknown), American cemetery

First American Protestant church established in Iran (1853)

Built by Joseph Cochran, this tiny church in Seir was the first erected by American Presbyterian missionaries in Iran. A small congregation of Protestants — descendants of people converted by Americans — continues to worship here

Interior, first American church in Iran (1853)

Built by Joseph Cochran, this tiny church in Seir was the first erected by American Presbyterian missionaries in Iran. A small congregation of Protestants — descendants of people converted by Americans — continues to worship here

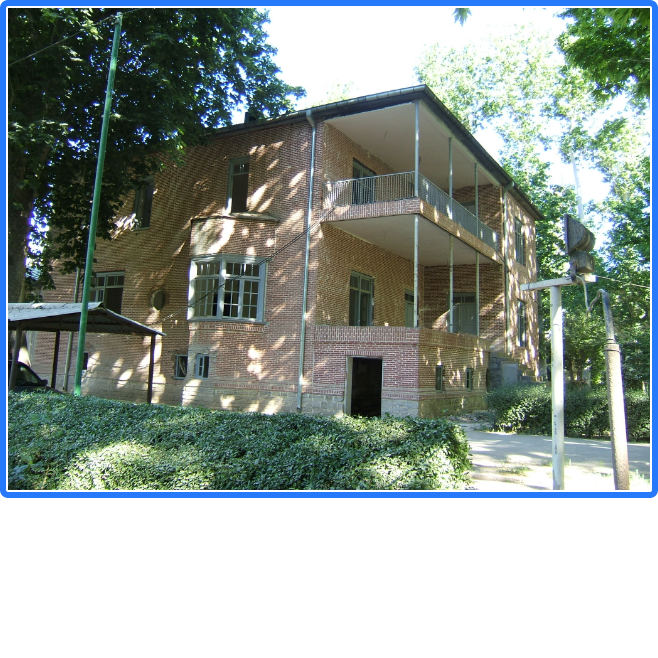

Medical college, Urmia

The first western-style medical college in Iran, this clinic and training school was established by the American medical missionary Joseph Cochran and his wife Katharine in 1878

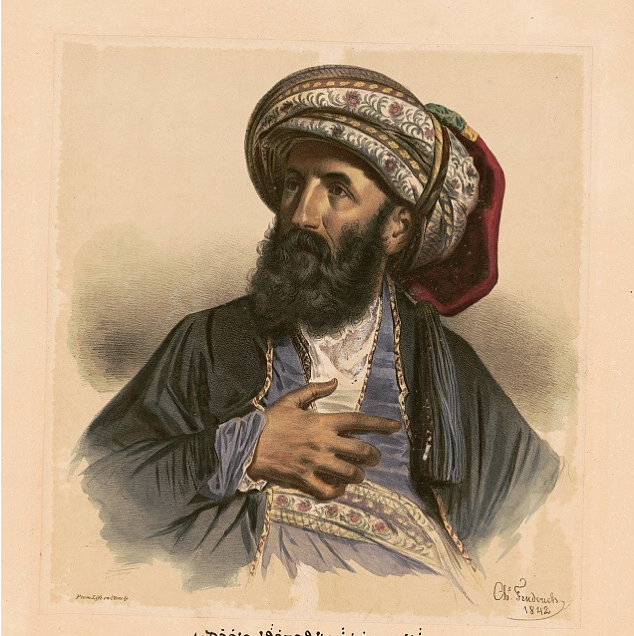

Mar Yohanan -- first Iranian in America (1841)

The earliest known Iranian visitor to the United States was Mar Yohanan — Assyrian Christian Bishop of Urmia. In 1841, Yohanan accompanied his friend Justin Perkins (the first American missionary to live in Iran) when the latter took a trip home to visit family. Together, the two men went on a speaking tour of New England, and drew huge crowds. Yohanan became a minor celebrity — known for wandering into rural taverns in his sumptuous robes and turban, and lecturing the bewildered locals — in his broken English — on the evils of drink.

(Library of Congress)

First Iranian ambassador to US (1888-9)

Hossein Qoli Khan Nuri, popularly known in Iran as “Hajji Washington”. The first Iranian minister (ambassador) to Washington, Nuri has long been an object of ridicule in his native Iran. However, archives reveal him to be a great admirer of the United States who performed his duty with dedication and passion. In one of his final despatches back to Tehran, he praised the US as a land where everything “that Allah and the Prophet Mohammad intended had finally come to fruition.”

The first Iranian Americans

Assyrian Christian immigrants in Chicago (1903). From the 1890s to the 1910s, the near north side of Chicago became home to a rapidly growing community of Christians from northwestern Iran.

(courtesy of Vasili Shoumanov)

Morgan Shuster, Treasurer-General of Iran (1911)

The 34-year-old Washington lawyer was hired by the Iranian government to bring order to the country’s finances following the Constitutional Revolution (mashruteh). In the process, he became passionate about the nationalist cause and boldly resisted Russian interference in Iran’s affairs. Though he lasted only seven months in the job, he became a hero to Iranians and a celebrity in the United States

(Library of Congress)

The king and the president (1943)

The 24-year-old shah bitterly resented Roosevelt’s refusal to pay him a courtesy visit while he was in Tehran for the Big Three summit with Stalin and Churchill. Eventually the shah gave up and went to the Soviet legation to call on FDR. The body language at that meeting—the first between US and Iranian leaders—speaks volumes about the direction that Iranian foreign policy was about to take under the new shah.

(Everett Collection Inc/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Shah in Washington (1949)

The first visit by an Iranian monarch to the United States, the shah’s November 1949 arrival took place against a backdrop of growing political protests and opposition back home

Mohammad Mosaddeq, Iranian prime minister (1951-53)

An ardent nationalist and democrat, Mosaddeq reached soaring heights of popularity with Iran’s growing population of young, modern and educated middle classes. After nationalising the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, he fought an epic feud with the British government. He was eventually brought down in a military coup funded and heavily choreographed by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

(Keystone-France/Getty Images)

Nixon in Tehran (1953)

The vice president goes to Iran in the immediate aftermath of the CIA-backed coup of 1953 to bolster the shah’s position and meet his new prime minister, Fazlollah Zahedi (r). His visit touched off days of protest that culminated in the shah’s forces shooting dead three students at Tehran University.

Eisenhower in Tehran (1959)

(Jack Garofolo/Getty Images)

Eisenhower in Tehran (1959)

The president’s motorcade travels down a route lined with flowers and Persian carpets

(Paul Slade/Getty Images)

Camelot: The Shah of Iran and Empress Farah visit Washington (1962)

JFK and the shah had an uneasy relationship. The US president constantly pushed the Iranian leader to consider reform and liberalization, but the shah felt Kennedy was naïve and idealistic and insufficiently appreciative of Iran’s need for military support against Communism. In April 1962, Kennedy invited the insecure shah to Washington to reassure him of US support. At the state dinner, to help ease tensions, the first lady pointedly wore a much smaller tiara than the one worn by the empress.

(Library of Congress)

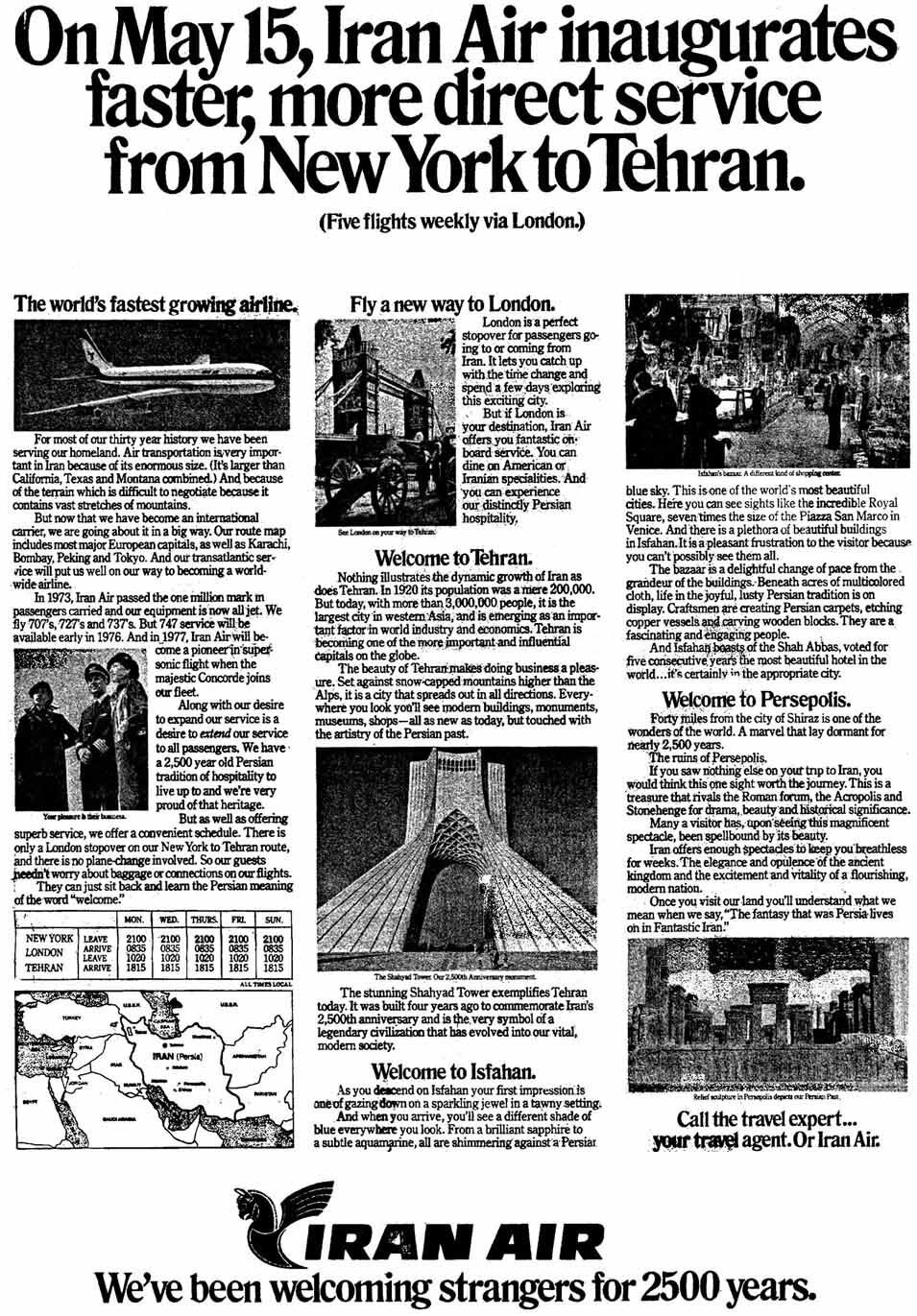

Iran Air advertisement (ca 1974)

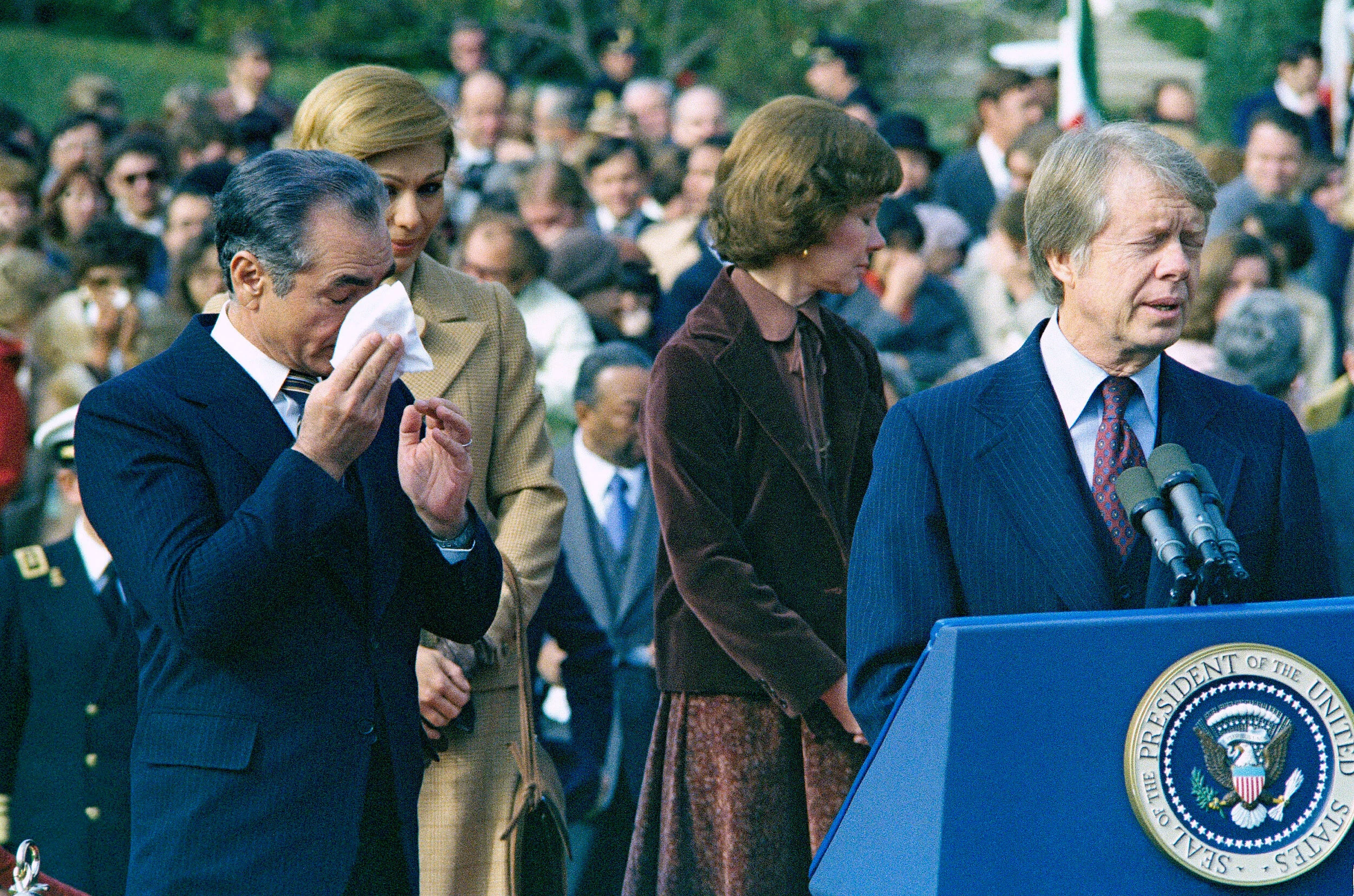

It would end in tears

The shah's final visit to Washington, November 1977, was marred by protests and embarrassment. At one point, teargas fired by Washington police to disperse protesters wafted into the eyes of the guest of honour and his hosts

(Associated Press)

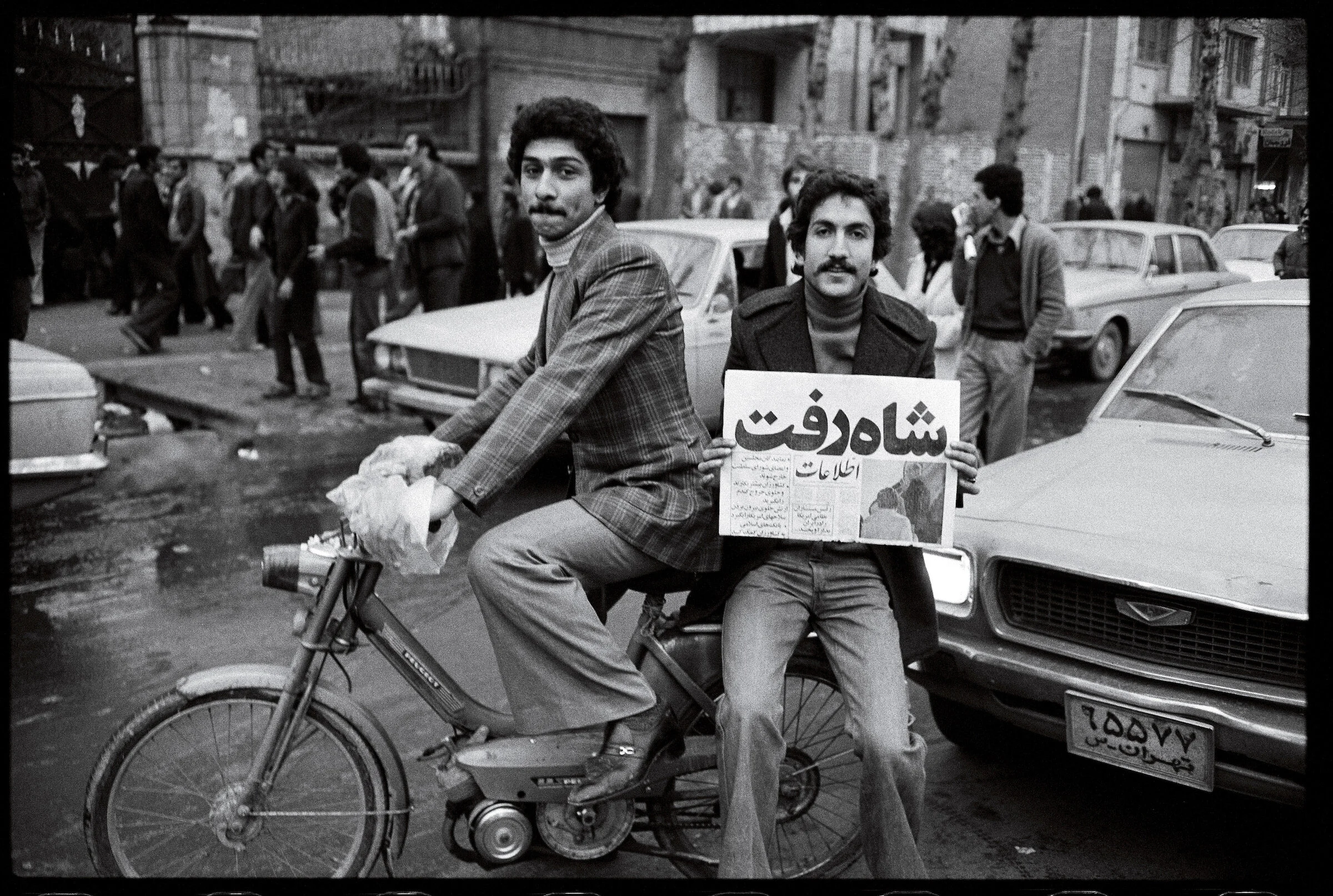

'The Shah Is Gone'

Jubilant Iranians hold up the iconic newspaper front page on the day the shah left Tehran, 16 January 1979

(David Burnett/Contact Press Images)

Khomeini returns to Iran (1979)

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini greets supporters the day after his return to Iran in February 1979. Exiled for fifteen years, the Ayatollah became the focal point of opposition to the shah in the 1960s and 1970s. When the monarchy was overthrown in the revolution of 1979, Khomeini returned to a rapturous welcome.

Alain Dejean/Getty Images

HOW IT STARTED

The author in Persepolis (2008)